Rainbow trout are native to the Pacific drainages of North America, ranging from Alaska to Mexico. Since 1874 it has been introduced to waters on all continents except Antarctica.

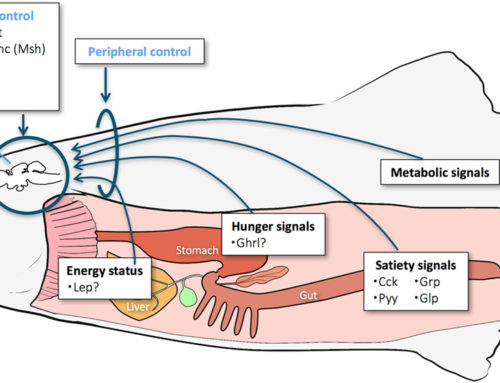

Habitat and biology

The rainbow trout is a hardy fish that is easy to spawn, fast growing, tolerant of a wide range of environments and handling, and the large fry can be easily weaned on to an artificial diet (usually feeding on zooplankton). Capable of occupying many different habitats, ranging from an anadromous life history [strain known as steelhead] (living in the ocean but spawning in gravel-bottomed, fast-flowing, well-oxygenated rivers and streams) to permanently inhabiting lakes. The anadromous strain is known for its rapid growth, achieving 7-10 kg within 3 years, whereas the freshwater strain can only attain 4.5 kg in the same time span. The species can withstand vast ranges of temperature variation (0-27 °C), but spawning and growth occurs in a narrower range (9-14 °C). The optimum water temperature for rainbow trout culture is below 21 °C. As a result, temperature and food availability influence growth and maturation, causing age at maturity to vary; though it is usually 3-4 years.

Females are able to produce up to 2,000 eggs/kg of body weight. Eggs are relatively large in diameter (3-7 mm). Most fish only spawn once, in spring (January-May), although selective breeding and photoperiod adjustment has developed hatchery strains that can mature earlier and spawn all year round.

Trout will not spawn naturally in culture systems; thus juveniles must be obtained either by artificial spawning in a hatchery or by collecting eggs from wild stocks. Larvae are well developed at hatching. In the wild, adult trout feed on aquatic and terrestrial insects, molluscs, crustaceans, fish eggs, minnows and other small fishes, but the most important food is freshwater shrimp, containing the carotenoid pigments responsible for the orange-pink colour in the flesh. In aquaculture, the inclusion of the synthetic pigments astaxanthin and canthaxanthin in aquafeeds causes this pink colouration to be produced (where desired).

Production systems

Rainbow Trout Production systems

Monoculture is the most common practice in rainbow trout culture, and intensive systems are considered necessary in most situations to make the operation economically attractive.

A potential site for commercial trout production must have a year-round supply of high quality water (1 l/min/kg of trout without aeration or 5 l/sec/tonne of trout with aeration). Ground water can be used where pumping is not required but aeration may be necessary in some cases. Supersaturated well water with dissolved nitrogen can cause gas bubbles to form in the blood of fish, preventing circulation, a condition known as gas-bubble disease. Alternatively, river water can be used but temperature and flow fluctuations alter production capacity. Where these criteria are met, trout are generally on-grown in raceways or ponds supplied with flowing water, but some are produced in cages and recirculating systems.

Seed supply

Development of broodstock

Trout will not spawn naturally in aquaculture systems, hence eggs are artificially spawned from high quality brood fish when fully mature (ripe); although two-year-old trout start spawning, females are seldom used for propagation before they are three or four years old. Generally, one male to three females is deemed a satisfactory sex ratio for broodstock. Males and females are generally kept separate. Some farms purchase eyed eggs from other sources; these should be ‘certified disease free’, although they should be treated with iodine (100 mg/litre for 10 min) upon arrival and gradually raised to the hatchery temperature. Broodstock are selected for fast growth and early maturation (usually after 2 years). One frequently used management tool is the use of sex-reversed, all-female broodstock to produce all-female progeny that grow faster. Functional males are produced by oral administration of the male hormone 17-methyl testosterone through starter feeds at the fry stage.

Stripping and fertilisation

Eggs are removed manually from females (under anaesthetics) by applying pressure from the pelvic fins to the vent area or by air spawning, causing the fish less stress and producing cleaner, healthier eggs. Insertion of a hypodermic needle about 10 mm into the body cavity near the pelvic fins and air pressure (2 psi) expels the eggs. The air is removed from the body cavity by massaging the sides of the fish. Up to 2 000 eggs/kg body weight are collected in a dry pan and kept dry, improving fertilisation.

Males are stripped in the same way as females, collecting milt in a bowl, avoiding water and urine contamination. Milt from more than one male (ensures good fertilisation) is mixed with the eggs. It is recommended that milt from three or four males is mixed prior to fertilisation to reduce inbreeding. Water is added to activate the sperm and cause the eggs to increase in size by about 20 percent by filling the perivitelline space between the shell and yoke; a process known as ‘water-hardening’. Fertilised eggs can be transported after 20 minutes, and up to 48 hours after fertilisation, but then not until the eyed stage (eyes are visible through the shell). Direct exposure to light should be avoided during all development stages, as it will kill embryos.

A technique that has been developed to improve production output is the use of monosex culture of females, or triploids. Triploidy is induced by exposing the eggs to pressure or heat whilst monosex are produced by fertilising normal female eggs (XX chromosomes) with milt from sex-reversed, masculinised females (XXX chromosomes). The mature testes of sex-reversed fish are large and rounded but have no vent. The testes are removed from the abdomen and lacerated to drain the milt into containers. An equal volume of extension fluid is added to make the sperm motile, and ready for fertilising normal ova. One advantage of this technique is that only the broodstock is sex-reversed, and they can be grown separately, while the marketed fish are not exposed to hormonal treatment.

Hatchery production

Eggs are incubated undisturbed until the eyed stage is reached, in hatching troughs, vertical flow incubators or hatching jars. Hatching and rearing troughs are 40-50 cm wide, 20 cm deep, and up to about 4 m in length. They usually have 2 layers of eggs placed in wire baskets or screened trays (California trays) supported 5 cm above the bottom, and water passes through the tray (3-4 L/min). As the eggs hatch (4-14 weeks) the fry drop through the mesh to a bottom trough.

The alternative is vertical flow incubators (Heath incubators) that stack up to 16 trays on top of each other. A single water source flows (3-4 L/min) up through the eggs, spills over into the tray below, thus becoming aerated, allowing large numbers of eggs to hatch in a minimal amount of space and water. Sac fry can remain in trays until swim-up at about 10 to 14 days after hatching. Time taken for hatching varies depending on water temperature, taking 100 days at 3.9 °C and 21 days at 14.4 °C (about 370 degree days). Hatching jars, available commercially or constructed from a 40 L drum and PVC pipe, introduce water from the bottom and flow from the top. 50 000 eggs can be incubated inexpensively suspended in a water flow that rolls the eggs, provided that the incubator contains two-thirds of the incubator volume in eggs, and the flow rate lifts the eggs 50 per cent of their static depth. In all the above methods dead eggs are removed regularly to limit fungal infection. Fungal infections can be controlled using formalin (37 percent solution of formaldehyde) in the inflow water at 1:600 dilution for 15 minutes daily, but not within 24 hours of hatching. Upon reaching the eyed stage addling (dropping eggs 40 cm) removes weak and undeveloped eggs.

Trout hatch (typically 95 per cent) with a reserve of food in a yolk sac (which lasts for 2-4 weeks), hence are referred to as yolk-sac fry, or alevins. Hatching of the batch of eggs usually takes 2-3 days, during which time all eggshells are regularly removed, as well as dead and deformed fry. Eggs incubated separately from rearing troughs are transferred to rearing troughs after hatching. After hatching, the trays are removed and trough water depth is kept shallow (8-10 cm) with a reduced flow until fry reach ‘swim-up’ stage, the yolk sac is absorbed, and active food searching begins.

Rearing fry

Fry are traditionally reared in fibreglass or concrete tanks, preferably circular in shape, to maintain a regular current and uniform distribution of the fry, but square tanks are also found. Tanks are usually 2 m in diameter or 2 x 2 m square, with depths of 50-60 cm. Water is delivered to the side of the tank using an elbow pipe or a spray bar to create a circulation of water. The drain is in the centre of the tank and is protected by a mesh screen. This position ensures that the water forms a vortex towards the centre that accumulates wastes for easy removal. The sump or drain pipe is connected to an elbow pipe on the side of the tank that can be used to regulate water level.

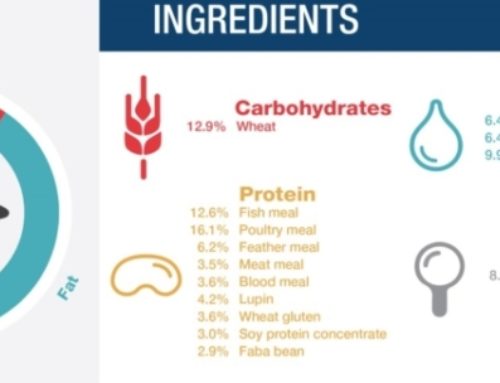

Fry are fed specially prepared starter feeds using automatic feeders, starting from when approximately 50 percent have reached the swim-up stage. When most fish are actively feeding, 10 percent of the fish weight should be introduced daily for 2-3 weeks, preferably on a continuous basis using clockwork belt feeders. The feed pellets, made of fish meal (80 percent), fish oils and grains, provide nutritional balance, encouraging growth and product quality, and are formulated to contain approximately 50 percent protein, 12-15 per cent fat, vitamins (A, D and E), minerals (calcium, phosphorus and sodium) and a pigment to achieve pink flesh (where desirable). High-energy commercial feeds and good feeding practices yield FCRs as low as 0.8:1. When the fry are 15-25 mm long feeding is based on published charts, related to temperature and fish size. Automatic feeders are useful but hand feeding is recommended in the early stages to ensure overfeeding does not occur, although demand feeders are more efficient for larger fish. As growth continues, dissolved oxygen is monitored and fish moved to larger tanks to reduce density.

Ongrowing techniques

Raceway and pond layout

When fry reach 8-10 cm in length (250 fish/kg) they are moved to outdoor grow-out facilities. These can comprise concrete raceways, flow-through Danish ponds, or cages. Individual raceways and ponds are typically 2-3 m wide, 12-30 m long and 1-1.2 m deep. Raceways provide well-oxygenated water and water quality can be improved by increasing flow rates; however, the stock is vulnerable to external water quality, and ambient water temperatures significantly influence growth rates. The number of raceways or ponds in a series varies with the pH [low pH (6.5-7.0) reduces unionised ammonia concentration] and the slope of the land (a 40 cm drop between each raceway is necessary for aeration). A typical raceway or pond layout is shown above. For hygiene, water quality, and controlling disease problems the parallel design is better, as any contamination flows through only a small part of the system. Fry are stocked in both systems at 25-50 fry/m² to produce up to 30 kg/m² with proper feeding and water supply, although higher production is possible.

Fish are grown on to marketable size (30-40 cm), usually within 9 months, although some fish are grown on to larger sizes over 20 months. The stock is graded, usually four times (at 2-5 g, 10-20 g, 50-60 g and >100 g) in a production cycle (first year), when the density needs to be reduced, thus ensuring fast growth, improving feeding management and creating product uniformity. Fish quantity and size sampling (twice a month) allows estimations of growth rates, feed conversions, production costs, and closeness to carrying capacity to be calculated; essential considerations for proper farm management.

Alternative on-growing systems for trout include cage culture (6 m by 6 m by 4-5 m deep) production systems where fish (up to 100 000) are held in floating cages in freshwater and marine (past fingerling stage) environments, ensuring good water supply and sufficient dissolved oxygen. This method is technically simple, as it uses existing water bodies at a lower capital cost than flow-through systems; however, stocks are vulnerable to external water quality problems and fish eating predators (rats and birds), and growth rates depend on ambient temperature. High stocking densities can be achieved (30-40 kg/m²) and fish transferred to marine cages have faster growth rates, reaching larger market size. Fry of about 70 g weight can attain 3 kg in less than 18 months.

Feed supply

Feeds for rainbow trout have been modified over the years and cooking-extrusion processing of foods now provide compact nutritious pelleted diets for all life stages. Pellets made in this way absorb high amounts of added fish oil and permit the production of high-energy feeds, with over 16 percent fat. Dietary protein levels in feeds have increased from 35-45 percent and dietary fat levels now exceed 22 percent in high energy feeds. Feed formulations for rainbow trout use fish meal, fish oil, grains and other ingredients, but the amount of fish meal has reduced to less than 50 percent in recent years by using alternative protein sources such as soybean meal. These high energy diets, are efficiently converted by the rainbow trout, often at food conversion ratios of close to 1:1. Feeding methods vary for production systems. Hand feeding is suitable for small fish eating fine food. Mechanical feeders, driven by electricity or solar power, are frequently used to feed set amounts at set intervals depending on fish size, temperature and season. Demand feeders can be used for fish greater than 12 cm.

Harvesting techniques

Methods of harvesting vary but water levels in the holding facilities are generally lowered and the fish netted out. In pens and cages, the fish are crowded using sweep nets and are either pumped from the holding pen alive and transported to the slaughter plant, generally by well boat, or slaughtered on the side of the pens. The whole process is carried out with the aim of keeping stress to a minimum, thus maximising flesh quality.

Handling and processing

Fish intended for restocking for angling purposes are handled carefully and checked for fin quality, size and any external signs of disease before being put into a special pond to await transport. Fish destined for the table are killed humanely after similar, but less stringent, checks. Before slaughter, all fish should be starved for 3 days and, once killed humanely, the head should be left on; beheaded fish spoil more quickly. Rainbow trout are supplied to markets either fresh or frozen, and their shelf life is 10-14 days if kept on ice. Trout are marketed as gutted whole fish, fillets (often boneless), or as value-added products, such as smoked trout.

Production costs

As with any business, rainbow trout farms aim to increase revenue and reduce expenditure. This can be done by using the best value feed/seed and materials, and achieving an efficient FCR. The average cost of production is between USD 1.20 and 2.00/kg. Running costs can start at USD 100 per 1 000 fry purchased at 6-8 cm and feed for one year from USD 1 000-1 400. Veterinary and medicine costs are from USD 50/tonne with transportation and sales commission about USD 500/tonne.

Diseases and control measures

There are a variety of diseases and parasites that can affect rainbow trout in aquaculture, which are summarised in the table below. Prevention is the most important measure; good hatchery sanitation by restricting access, installing disinfectant footbaths and disinfecting equipment reduces the exposure of vulnerable fish to disease-causing agents.

In some cases antibiotics and other pharmaceuticals have been used in treatment but their inclusion in this table does not imply an FAO recommendation.

| DISEASE | AGENT | TYPE | SYNDROME | MEASURES |

| Furunculosis | Aeromonas salmonicida | Bacterium | Inflammation of intestine; reddening of fins; boils on body; pectoral fins infected; tissues die back | Antibiotic mixed with food, e.g. oxytetracycline |

| Similar to furunculosis | Aeromonas liquefaciens | Bacterium | Smaller lesions on body that become open sores; fins become reddened and tissues break down | Same treatment as furunculosis |

| Vibriosis | Vibrio anguillarum | Bacterium | Loss of appetite; fins and areas around vent and mouth become reddened; sometimes bleeding around mouth and gills; potential high mortality | Same as furunculosis, plus vaccine for greater protection |

| Bacterial kidney disease (BKD) | Corynebacterium | Bacterium | Whitish lesions in the kidney; bleeding from kidneys and liver; some fish may lose appetite and swim close to surface; appear dark in colour | Same as furunculosis |

| Bacterial gill disease | Myxobacterium | Bacterium | Loss of appetite; swelling and reddening of gills; eventually gill filaments mass together and become paler with a secretion blocking gill function in later stage | Bathing in bacteriocide and regular filtering of water supply to remove particles in water |

| Infective Pancreatic Necrosis | IPN | Virus | Erratic swimming, eventually to bottom of tank where death occurs | No treatment available; eradicate disease by removal of infected stock |

| Infective Haematopoietic Necrosis | IHN | Virus | Erratic swimming eventually floating upside down whilst breathing rapidly after which death occurs; eyes bulge; bleeding from base of pectoral fins, dorsal fin and vent | As above |

| Viral Haemorrhagic Septicaemia | VHS | Virus | Bulging eyes and, in some cases, bleeding eyes; pale gills; swollen abdomen; lethargy | As above |

| White spot | Ichthyophthirius multifilis | Protozoan | White patches on body; becoming lethargic; attempt to remove parasites by rubbing on side of tank | Formalin bath for surface parasites; copper sulphate for parasites below surface; prevented by fast-flowing water |

| Whirling disease (Myxosomiasis) | Myxosoma cerebralis | Protozoan | Darkening of skin; swimming in spinning fashion; deformities around gills and tail fin; death eventually occurs | No treatment; fish must be kept out of infected water; water treated with calcium cyanamide |

| Hexamitaisis Octomitis | Hexamita truttae | Protozoan | Lethargic, sinking to bottom of tank where death occurs; some fish make sudden random movements | Feed calomel with food |

| Costiasis | Costia necatrix | Protozoan | Blue-grey slime on skin which contains parasite | Formalin bath |

| Fluke | Gyrodactylus sp. | Trematode | Parasites attached to caudal and anal fins; body and fins erode, leaving lesions that are attacked by Saprolegnia | Formalin bath |

| Trematodal parasite | Diplostomum spathaceum | Trematode | Eye lens cloudy; loss of condition | No treatment available. Water supply kept clear of snail hosts |

Suppliers of pathology expertise

Each producing country has a government authority responsible for upholding statutory requirements, such as licensing, discharge control, notifiable disease control, etc. Contact the relevant government aquaculture/fisheries/animal health departments. The supply of diagnostic services may be carried out by government departments or private organizations or individuals.

Statistics

Production statistics

The production of rainbow trout has grown exponentially since the 1950s, especially in Europe and more recently in Chile. This is primarily due to increased inland production in countries such as France, Italy, Denmark, Germany and Spain to supply the domestic markets, and mariculture in cages in Norway and Chile for the export market. Chile is currently the largest producer. Other major producing countries include Norway, France, Italy, Spain, Denmark, USA, Germany, Iran and the UK.

Market and trade

There are many outputs from rainbow trout culture, which include food products sold in supermarkets and other retail outlets, live fish for the restocking of rivers and lakes for recreational put-and-take game fisheries (especially in the USA, Europe and Japan), and products from hatcheries whose eggs and juveniles are sold to other farms.

Products for human consumption come as fresh, smoked, whole, filleted, canned, and frozen trout that are eaten steamed, fried, broiled, boiled, or micro-waved and baked. Trout processing wastes can be used for fish meal production or as fertiliser. The fresh fish market is large because the flesh is soft and delicate, white to pink in colour with a mild flavour. Food market fish size can be reached in 9 months but ‘pan-sized’ fish, generally 280-400 g, are harvested after 12-18 months. However, optimal harvest size varies globally: in the USA trout are harvested at 450-600 g; in Europe at 1-2 kg; in Canada, Chile, Norway, Sweden and Finland at 3-5 kg (from marine cages). Preferences in meat colour also vary globally with USA preferring white meat, but Europe and other parts of the world preferring pink meat generated from pigment supplements in aquafeed.

Strict guidelines are in place for the regulation of rainbow trout for consumption with respect to food safety. Hygiene and safe transportation of fresh fish are of paramount importance, to ensure that fish are uncontaminated by bacteria, in accordance with food agency directives.

Status and trends

The rainbow trout farming industry has been developing for several hundred years, and many aspects are highly efficient, using well-established systems. However, current research and development is continually attempting to increase production efficiency and sales by increasing rearing densities, improving recirculation technology, developing genetically superior strains of fish for improved growth, controlling maturation and gender, improving diets, reducing phosphorous concentrations of effluents, and developing better marketing. One method that has been developed is a genetically modified hormone that is effective in reducing production costs. However, problems may lie ahead as public opinion towards genetically-modified products continues to be negative. As production continues to rise research is needed to keep costs to a minimum so the industry can move forward.

Main issues

Trout farms inevitably impact upon the environment as river water is diverted from its natural course, potentially altering species composition and diversity. Escapee trout from farms can have negative impacts, potentially displacing endemic species (especially brown trout), and exhibiting aggressive behaviour that results in the altering of fish community structure.

Impacts from flow-through systems are largely from disease treatment chemicals, uneaten feed and fish excreta, which can alter water and sediment chemistry downstream of the farm. Elevated nutrients reduce water quality (increasing biological oxygen demand, reducing dissolved oxygen and increasing turbidity) and increase the growth of algae and aquatic plants. Output restrictions require farms to have settling areas to remove solid wastes, though soluble phosphorous in the effluent cannot be removed economically – hence reductions in feed are needed to address the problem. There are also problems with the transmission of diseases from farmed stock to vulnerable wild populations.

Responsible aquaculture practices

Trout farming is generally conducted responsibly. Trout farmers are encouraged to adhere to the principles contained in the FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries and the FAO Technical Guidelines for Responsible Fisheries (Aquaculture Development).

References

Bonnieux, F., Gloaguen, Y., Rainelli, P., Faure, A., Fauconneau, B., le Bail, P.Y., Maisse, G. & Prunet, P. 2002. The case of growth hormones in French trout farming. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 43:369-379.

Boujard, T., Labbe, L. & Auperin, B. 2002. Feeding behaviour, energy expenditure and growth of rainbow trout in relation to stocking density and food accessibility. Aquaculture Research, 33:1233-1242.

Hardy, R.W., Fornshell, G.C.G. & Brannon, E.L. 2000. Rainbow trout culture. In: R. Stickney (ed.) Fish Culture, pp. 716-722. John Wiley & Sons, New York, USA.

Pillay T.V.R. 1990. Aquaculture Principles and Practice. Fishing News Books (Blackwell Science), Oxford, England. 575 pp.

Purser, J. & Forteath, N. 2003. Salmonids. In: J.S. Lucas & P.C. Southgate (eds.), Aquaculture: farming aquatic animals and plants, pp. 295-320. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, England.

Scottish Executive Central Research Unit. 2002. Review and synthesis of the environmental impacts of aquaculture. The Stationery Office, Edinburgh, Scotland. 80 pp.

Sedgwick, S.D. 1990. Trout Farming Handbook 5th edition. Fishing News Books (Blackwell Science), Oxford, England. 192 pp.

Shepherd, J. & Bromage, N. 1992. Intensive Fish Farming. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, England. 416 pp.

Stevenson, J.P. 1987. Trout Farming Manual 2nd edition. Fishing News Books, Farnham, England. 186 pp.

Related links

- Database on Introductions of Aquatic Species – DIAS

- FAO FishStatJ – Universal software for fishery statistical time series

- http://www.fao.org/fishery/culturedspecies/Oncorhynchus_mykiss/en